‘En plantant la pointe de nos bâtons dans le sol pour le repousser derrière nous, en file ininterrompue et obstinée, nous, les pèlerins de Saint-Jacques, depuis des siècles, nous faisons tourner la terre’.1

The pilgrim slogging along a road, towards a place somewhere in the distance, is one of the most fascinating and universal images of what it means to be human. Portraying the individual as small and lonely in a big world, relying on the power of body and spirit/will.2 The pilgrimage is a fundamental way of walking, walking in search of something untestable. In Latin peregrinus means 'stranger'. The pilgrim voluntarily transforms himself into someone who is a stranger wherever he passes.3

The pilgrimage presupposes an archaic view of space. A sacred geography; in which the world is not a whole of neutral points, but contains qualitative differences. A certain charge, a force, energy or aura, which is 'sacred'. Those sacred places, fall into two different categories: 'natural', like mountains, springs, rivers, caves, lakes and islands (peninsulas). Or cultural (human history).

Holy places can be found in almost every religion; from Mecca, the Ganges (at Benares), Lhasa Tibet, the Athos Mountains in Greece (for Greek Orthodox Christianity and François Augiéras) all attract pilgrims. For Christianity Jerusalem, Rome, Santiago, Canterbury. And various ‘Maria sightings’, most famously Lourdes or Our Lady of La Salette (She who weeps; considered superior by Leon Bloy).

Before the year 813 ( a year before the death of Charlemagne), there was no mention of St James (the Great), in Spain nor elsewhere. Then a hermit had a vision, in a dream angels revealed to him the presence of St James. A marble grave containing bones, immediately identified as those of St James and two of his disciples, were found at a place known as Compostela.4 Which could be translated as ‘field of the star’ (but more likely resonates the Latin compositum tellus; a graveyard).5 More on the myth of St James and the pre-Christian ‘pagan’ uses of the site later. Suffice to say the site became one of Medieval Europe’s (if not the) most important pilgrimage sites.

The pilgrimage to Compostela declined from 16th century onward, to experience a remarkable revival in the 1960’s and 70’s. Remarkable because at the same time secularization across Europe increased. In 1984, 500 pilgrims were registered, in 1988, 3500. Then things took off, in 1993 a 100,000, in 2013 some 200,000 and in 2017 as many as 300,000 ‘pilgrims’ arrived. According to a recent BBC article 2024 is expected to be the busiest year yet, after 446,000 registered arrivals in 2023.6

In 1984 it was proposed ‘a cultural property belonging to Europe’ and in 1987, ‘to promote a spirit of peace between Europeans through awareness of their shared history’, was officially recognized under The Cultural Itineraries of the Council of Europe.7

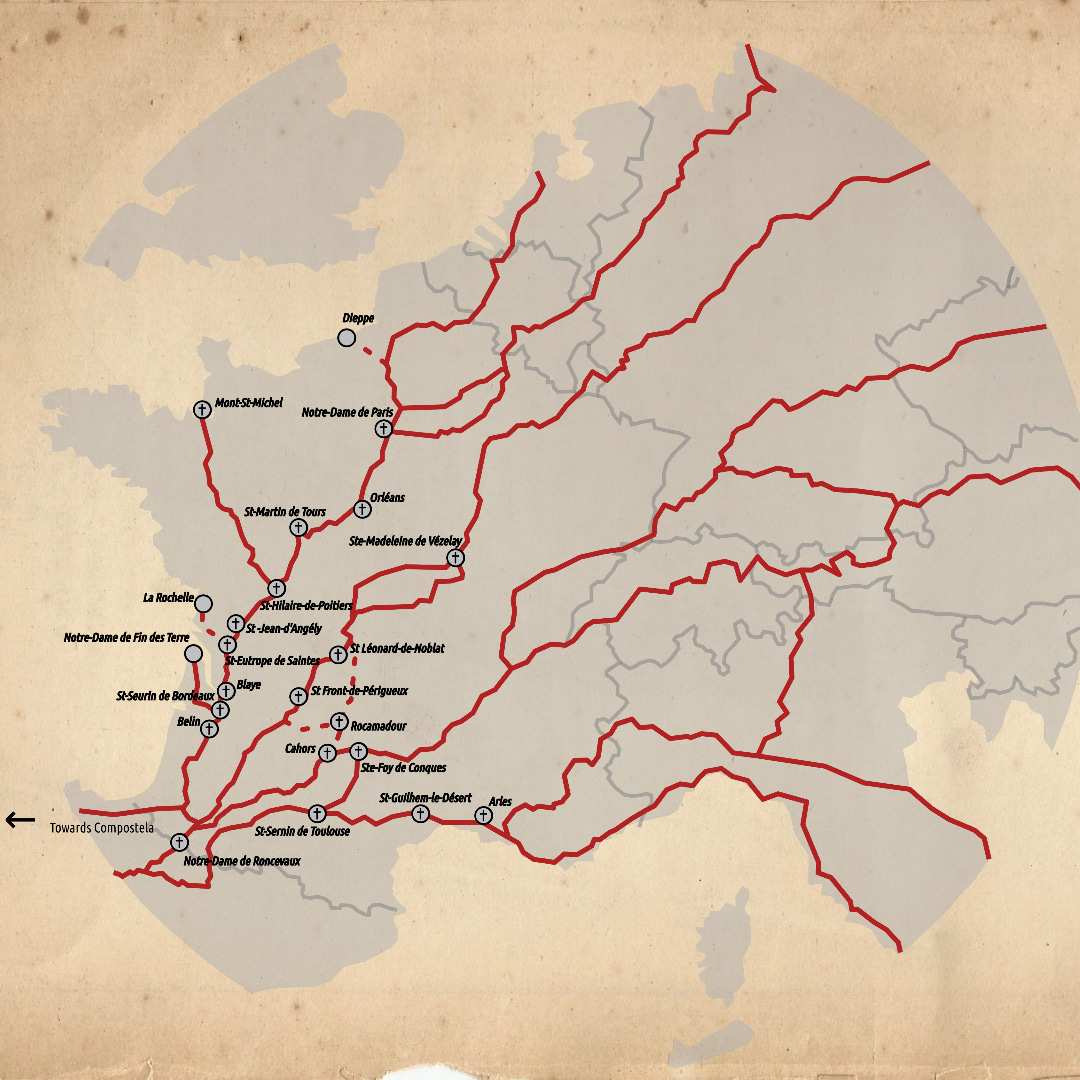

God was largely absent from this revival. To obtain your credential, the pilgrim's passport, you must fill out a questionnaire and define your motivation by checking one of four boxes: religious, spiritual, cultural or sporting. Motivations are split into 20% religious, 30% spiritual, 30% cultural and 20% sporting. In 1998 the ensemble of ‘Routes of Santiago de Compostela in France’ was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List for its ‘Outstanding Universal Value’.8

Medieval pilgrimage

Aymeri Picaud’s 1130 ‘Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago’ is a practical, unsentimental, and often quite opinionated first-person narrative of pilgrimage to Santiago. His comments on the terrain, food and wine, the detestable habits of the natives, monuments of note and liturgical practices at the shrine were invaluable to the medieval pilgrim, and the first of numerous that followed.

A study of medieval journals gives an insight into the motivations and experiences of the early pilgrims. ‘Cursed be their boatmen!’, exempt from toll in principle, Aymeri Picaud dooms them to the same hell as smugglers. Three and a half centuries later, Jean de Tournai in turn discovered the rapacity of the toll collectors: not much had changed.9

A great pilgrimage promised the best assurance for eternal life: by the duration of the journey, by the number of relics venerated along the way, of sanctuaries visited the pilgrim obtained ‘indulgences’ (a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo to be forgiven ones sins i.e. time spend in purgatory). Alternatively a poor person could undertake the journey in the name (and at expense of another, sometimes provisions for this were made as part of a testament). For some the pilgrimage became a profession: Pilgrim by proxy.

St James is one of the two apostles whose tomb can be found in the West (after Peter in Rome). And perhaps Rome lacks being at the end of an ancient Celtic path, at the extreme end of the land… William of Aquitaine, after being accused by Bernard of Clairvaux (St Bernard), of having encouraged heresy is exemplary for the penitent pilgrim. A special grace allowed him to die on his arrival at the shrine (April 9, 1137), a Good Friday, after having confessed.

The sick (on behalf of themselves or loved ones), either grateful after they were cured or to seek healing, flocked there. The ‘Knights of Saint-Lazare’, recognizable by their white coats with green crosses especially took care of the lepers, living separately, even on the path. These ‘orders of chivalry’; most famously the order of the Temple and the order of Saint-Jean-de-Jerusalem (known as the Order of the Hospital). Came into existence in the aftermath of the first crusade.10

Their mission was in the Holy Land, but the generosity of the faithful provided them with domains in the west. These commanderies (centers of land exploitation) had dimensions as diverse as the generosity. They will be a subject to explore in the future. The Knights Templar, in their white coats with vermilion crosses, originally dedicated their lives, their fortune and their swords to protect the pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. They extended their attention to Santiago, as did the Knights of the Hospital, in their black coats with white crosses. Later joint by the white coats with black crosses of the Teutonic Knights.

In northern Europe, Flanders and the Netherlands, you could be condemned to pilgrimage, as a form of ‘salutary transformation through banishment’. Some had to walk in chains to aggravate their penance. Chains, rings, balls, shackles: to be worn until the metal corroded by sweat, rust and wear freed the penitent and the sin has been atoned for.

Before Departure

As the journey was long and perilous, the pilgrim had to put his affairs in order, go to confession, find money for the trip and have your bag and staff blessed. The true attributes of the Compostela pilgrim:

The bag (or pera of the manuscripts), contains the food, passports and certificates of the pilgrim.

The staff (or bourdon), is a strong piece of wood almost two meters high, equipped with an iron point. This ‘spiritual sword’ also helps with walking and serves for defense against wolfs and dogs. The bourdon often had the gourd for water or wine attached, and ‘the shell’ when returning (returning from Jerusalem the pilgrim carries the palm).

The pilgrim was sanctified by his enterprise; by protecting him, by assisting him, it is Jesus himself who we assist and protect (‘He who receives you receives me’).11

This post will continue in: Santiago de Compostela. Part 2: The original path.

‘By planting the tips of our sticks in the ground to push it back behind us, in an unbroken and stubborn line, we, the pilgrims of Santiago, have for centuries been making the earth turn’.

Sant-André de A., 2010. En avant, route! Éditions Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-012837-2

Solnit R., 2019 (2001). Wanderlust, Een filosofische geschiedenis van het wandelen. (original English title = Wanderlust: A History of Walking) Nijgh & Van Ditmar. ISBN: 9-78-90-388-0680-8

Lemaire T., 2019. Met lichte tred, De wereld van de wandelaar (≈ With light steps, The world of the walker). Ambo/Anthos. ISBN 978 90 263 4787 0

Barret P. et Gurgand J-N., 1985 (1978). Priez pour nous à Compostelle. Hachette, Le livre de poche. ISBN 2-253-02399-X

Greenia, G., 2016. Santiago de Compostela. Europe: A Literary History of Europe, 1348-1418 (pp. 94-101). Oxford University Press. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters/67

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20240605-the-portuguese-pilgrimage-you-should-do-in-2024 As last accessed 11/06/2024.

https://www.chemins-compostelle.com/en/europ Last accessed on 18/05/2024.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/868/ Last accessed on 18/05/2024.

Barret P. et Gurgand J-N., 1985 (1978). Priez pour nous à Compostelle. Hachette, Le livre de poche. ISBN 2-253-02399-X

Favier J., 2004. Les Plantagenêts, Origines et destin d’un empire Xie-XIVe siècle. Éditions Tallandier, Collection Texto Le goût de l’histoire. ISBN 979-10-210-0881-6

“Anyone who welcomes you welcomes me, and anyone who welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me. Whoever welcomes a prophet as a prophet will receive a prophet’s reward, and whoever welcomes a righteous person as a righteous person will receive a righteous person’s reward. And if anyone gives even a cup of cold water to one of these little ones who is my disciple, truly I tell you, that person will certainly not lose their reward.”

Matthew 10:40-42, Bible, New International Version